Be careful around daydreams, particularly those that won’t go away or leave you alone. They can become intrusive, and at some point will demand to be dealt with. Before I set off down the river, I worked on the night stock crew at Hy-Vee Number One Grocery Store in Ames, Iowa. I had too much time to daydream.

My mom, three of my sisters and I all worked at Hy-Vee Number 1 in Ames, Iowa. Hy-Vee treats its employees well.

The job could be mind-numbing. Several nights a week, I punched the time clock, then, along with several others, started the work of placing several tons of merchandise on the shelves. There was a routine to the job that never seemed to change.

The stacks of cases would be wheeled out on the floor, and placed strategically in the middle of the aisle. Each stocker generally worked in the same aisles. I picked up a case, marked the contents with a pricemarker, and arranged the items neatly on the shelf. This routine went on for hours, and I worked quickly, efficiently and without much intellectual investment.

Over everything was a never-ending sound track of Lawrence Welk-type instrumentals, piped in over the store PA system. The lyrics included a series of idiotic la-la-las, and do-do-dos. Hearing the same “music” over and over, over an eight-to-10-hour shift, was enough to make me want to run screaming down the aisle and climb one of the precisely-built end displays. I threatened to do that, more than once. The other workers encouraged me.

But usually, we worked steadily, and there wasn’t time for a lot of conversation. The pay was good, and there were plenty of enjoyable times, like when the bakers, early in the morning, started the doughnut machine. There were always a few that weren’t pretty enough to sell, and those were reserved for the stock crew.

So, somewhere during the stock shifts, the Mississippi started to intrude. I’d think about books I’d read, and for some reason, “Life on the Mississippi” and “Huckleberry Finn.”

I first read about the river when I was a kid. Ethel Weston, who was about 80 at the time, lived down the road from my parents’ farm. When her husband died, the neighbors all looked out for her. I did stuff for Mrs. Weston. I killed sparrows in her barn with my BB gun, helped throw down hay from the loft for her sheep, moved things and mowed her lawn.

Mrs. Weston always had lemonade for me when I was done mowing, but more importantly, she gave me access to her extensive library of books. She would recommend and loan books to me.

The next week, after the lawn mowing was done, we’d drink lemonade and talk books. That was where I learned first about Tom Sawyer, and heard about this Huckleberry Finn guy.

But the idea of floating down the Mississippi was literally born in Aisle One, somewhere in the canned juice section. And it might have quietly died there too, except for a conversation that involved too much beer.

Andy Michalicek, a former roommate of mine at Iowa State, was passing through Ames one night in 1979 and we went out to the bars after I got off work. We both graduated from Iowa State the same quarter. Andy got his master’s degree in electrical engineering and went to work as an engineer in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

After a couple beers, and about half tanked, I was expounding on what’s wrong with most people. I’d received another graduate school rejection that day, and it was starting to look like I wouldn’t get accepted anywhere. Frustration had set in.

“Do you know why most people aren’t happy with their lives?”

Andy didn’t have an opinion.

“Everything’s easy. People get out of school, get a job that pays well and before they know it, they’re in a rut,” I said. “It’s a comfortable rut. But somewhere along the line, they miss something that could have made them happy. Then they try to buy happiness, and take jobs they hate so they can buy toys. So they end up semi-happy, and life is never as much fun as it could have been.”

That was no great revelation – my life was starting to follow that pattern, and worse, it was getting easier to justify. I needed to buy a new car soon, and once I gave up the grad school idea, I’d start shopping. My continual reminder was that my job paid really well, and there was a lot of promotion potential.

Andy was amused.

“Are you talking about yourself?” he asked. “You have your degree, but you’re still in Ames, and still sacking groceries.”

Well, that was easy to explain. I could read the bottom line.

“I make twice as much, as low man on the totem pole in the grocery business, as I could as a journalist. A store manager, makes more money that any newspaperman,” I said. “Besides, sometimes, you can’t just go out and do what you’d like to.”

“And what might that be?”

Andy was humoring me. I was slamming beers with the enthusiasm of a frustrated blue collar worker on Friday night. Andy knew he’d be driving me home.

No thought was needed. Whenever life at the store felt particularly claustrophobic, the river intruded. There was no reason for that: I’d only seen the river about five times. But, I had traveled it many, many times with Huck, Jim and Tom.

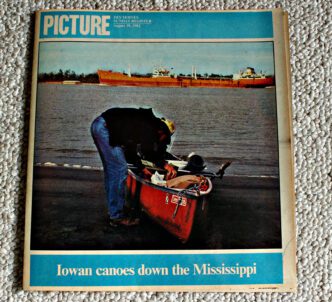

“The Mississippi River is America. There is nothing like it anywhere else in the world and there must be a distinct, unique culture along it. If a person did a solo in a canoe, he’d see it all,” I said. “Someday I want to get a canoe, set it in at the headwaters at Lake Itasca, and float to the Gulf of Mexico.”

Andy leaned a little forward, a lot more interested that I would have imagined.

“Why? Traveling is fine, but shouldn’t there be some point to it?” he asked. “And besides, a lot of people float down the Mississippi.”

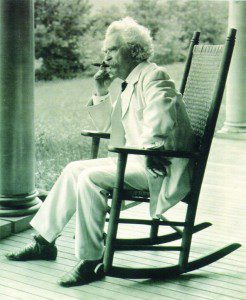

“I wouldn’t be a tourist. I’d camp on the river banks, meet the river people, and do a whole cultural immersion thing. I’d experience the river,” I boasted. “When I got done, I’d write a book about it and take up where Mark Twain left off!”

experience the river,” I boasted. “When I got done, I’d write a book about it and take up where Mark Twain left off!”

“So what would you do?” I asked. My pipe dream was going to be hard to top.

Andy ignored my question, and thought a moment.

“That’s a great idea,” he said. “Why don’t you go do the river?”

“Oh, I might some day,” I said. “I don’t have the money right

now.”

Andy though hard for a couple moments.

“I do,” he said, and looked sober as a judge. “I’m not rich, but I could stake you a few bucks.”

It was my turn to think hard for a few moments then. Our conversation took on a serious note as we discussed equipment, logistics and the potential for the next hour or so. Finally, we left so I could get some sleep before my next shift at the store.

“Most people would think this idea is so much beer talk,” I said. “Why would you want to be involved? Realistically, completing the voyage is a long shot, then writing a book is a longer shot, and getting it published is probably next to impossible. It’s not like this is a new idea.”

Andy just smiled and said he wanted to be part of an adventure. We paid the bill and headed out to the car.

###

Army Captain Willard Glasser claims to be the first to travel the length of the Mississippi in a canoe. He set out with an expedition of several canoes for an undertaking second in size only to his ego. During that 1879 voyage, his group stopped in river towns and gave lectures at sold-out theaters and Opera Houses.

At the end of the journey, Glasser wrote “Down the Great River” and embarked on a highly successful lecture tour. He was looked upon as a most daring individual, and his feat of canoeing the Mississippi was viewed as a very dangerous undertaking.

Glasser had basically the same idea I had: ” … to become familiar with the most striking features of the mighty river, and to study, through personal intercourse, the varying phases of life and character along its banks.” (Down the Great River, page 78)

To make the tale even better, Glasser invented all sorts of adventures, some involving river features that didn’t exist. Glasser figured his lies would remain unknown, because he commented:

“… it would hardly be probable that anyone would attempt the trip again, for the perils of a voyage of over 3,000 miles in an open boat are not purely imaginary.”

There were several reasons why I wanted to travel by canoe, and that’s where the trip planning started. First and foremost, a canoe was affordable and could be handled easily by a single paddler.

Eventually, I decided on a 15-foot Coleman, made out of a plastic/fiberglass material that was ordered out of the J.C.Penney’s’ catalog. Once I got to St. Paul, Minnesota, where the Mississippi becomes a big river, I would attach a Grumman rowing rig and equip the canoe with oars.

There were other reasons, too. A boat and motor would have been a more efficient way to travel, but outboards require gas, marina gas stations, and money. I didn’t want to worry about re-fueling stops or mechanical breakdowns.

Another reason was purely philosophical. I enjoy traveling under my own power, and believe walking is the best way to

I still use the 15-foot canoe that carried me all the way to the gulf. Here, Belle and I are in my canoe on Oregon’s John Day River in 2008.

really see anything. A canoeist on the river would be as free as a hiker in the mountains.

My travel philosophy came from one of my heroes, John Muir. He’d written: “Only by going alone in silence, without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of wilderness. All other travel is mere dust and hotels and baggage and chatter.”

The Mississippi is not wilderness, but Muir’s philosophy brought up another important aspect: Where to stay. Hotels or motels were out of the question, mostly because of the cost, but also because I would have to stay in a town every night. Then, my travel plans would revolve around where the next lodgings were, and I’d end up on a schedule. Any spontaneity would be gone.

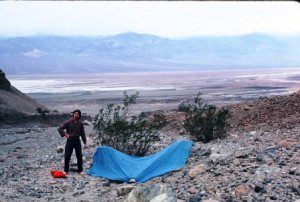

My gear needs were taken care of by my much-used backpacking equipment. My two-man dome tent came from a K-Mart, Blue Light Special and cost $40. My sleeping bag, a synthetic mummy bag and veteran of several summers of backpacking in the mountains, was warm down to about 15 degrees.

I cooked on my Svea 123 backpacking stove, in pots and pans I’d acquired in college. Everything was packed in four waterproof five-gallon frosting buckets the Hy-Vee bakers gave me. My cameras, film and wallet were packed in waterproof Army surplus ammunition boxes. A medium-sized insulated ice chest would carry whatever perishables I needed, as well as acting as a dry box for other gear.

Clothing was whatever I had, since cold weather shouldn’t be a problem. I bought a rainsuit, and a few other items, but my river travel garb for most of the journey ended up being gym shorts and a short-sleeved cotton shirt. On many summer days, I’d wear gym shorts, a life vest and a hat.

A broad-brimmed hat, my first choice for sun protection, would have blown off in the wind, so I ended up with an Iowa State baseball cap.

There was another requirement: the trip would have to be a solo. Henry David Thoreau commented once: “I have never found a companion as companionable as solitude.”

Well, I have. Several in fact, but none of them could go.

My first choice would have been John Nerness, my best friend and backpacking buddy from college. We’d both worked at Hy-Vee in college and had hiked, backpacked and canoed many miles together. Also, John is a skilled outdoorsman who stayed in great physical shape and was always ready for an adventure.

But the year before, John and a friend left their jobs as design engineers at Lockheed Aviation in Mountainview, CA to travel through Europe. He couldn’t take any time off for my river summer.

But the Upper Mississippi’s current is very slow. I’d have to get another paddler’s help or spend all summer going through Minnesota. After considering several traveling companions, I finally settled on my 15-year old brother Michael. He jumped at the chance to go.

Initially, I had considerable doubts about taking Mike along. He had never been camping or canoeing, and was a typical urban adolescent, committed to junk food and television. He thought all fun outdoor activities were associated with some sort of gasoline consumption. He was also 20 pounds overweight and made no effort to get in shape

In the end, family ties overcame logic. Mike is the youngest of my seven siblings. Our Dad was 61 years old at the time, and couldn’t keep up with a 15-year-old. Subsequently, they never did much together. I filled in, taking Mike hunting and fishing whenever possible.

But I could see the potential. Mike would have a goal – of paddling from Lake Itasca to Minneapolis and I’d make sure he achieved it. Besides, he was going on a balanced diet as soon as we hit the river, and the exercise, outdoor living and nutritious food would do something positive.

The preparation for a long journey is enjoyable. The actual packing isn’t difficult. The mental preparation, though, is hard. While verbal plans sound good, and possibly even grandiose, reality sneaks in.

Toward the end of May, things and activities I took for granted started seeming very important. A hot shower in the morning, for example, would be a luxury, as would a comfortable place to sleep. Telephone booths and mail boxes might be hard to find.

There was also a young lady named Leslie I’d been taking for granted, and the closer the beginning of trip got, the dearer she seemed. Les had been the leading lady in my life for well over a year. She never tried to discourage me, but was clearly less than luke-warm about the idea. She would listen quietly to plans and preparations, and didn’t say much.

The departure date from Ames was set for June 7. The day before was consumed with last minute details. The small mountain of gear in my living room didn’t look like it would ever fit in a 15-foot canoe. Les left late that evening after supervising most of the day. She promised to come back in the morning to “see how you get all that junk in a car.”

I hardly slept that night. I kept getting up to check on something, or tossing and turning when I did go to bed. Subsequently, I was still up at dawn.

Leslie arrived about 7 a.m., shortly before the scheduled departure. We made futile attempts at small talk, and soon, she had to leave to go to work.

“I’m gonna miss you,” I said for the hundredth time as I walked her to her car. “But I’ll call as soon as I can, and I’ll write whenever I find a mailbox.”

She kissed me good-bye, then got in and rolled down the window. There was a little moisture at the corner of her eyes. Suddenly, I had the greatest urge to drop the whole idea and stay home. I could be back at work that afternoon…

“Well,” she said. “Don’t fall in the river.”

She drove off, and I stood in the street watching until her car went out of sight. Then I hurried back in. Andy would be there soon, and there was surely something I needed to check.

###

The sun was up barely half an hour by the time our two cars arrived at Lake Itasca State Park in northern Minnesota.

Everybody was tired after the all-night drive from Ames, but I was so excited I could hardly stand it. I lifted the canoe off the top of the car and raced in the direction the Park Service signs pointed. The forest smelled like the inside of a greenhouse after an all-night rain. The tall pines lined the path to where Lake Itasca sparkled in the sunlight. Then, around the bend, was my personal Mecca: The honest-to-God beginning of the Mississippi.

The sign beside the stream that flows out of the lake said it all.

Actually, the length of the Mississippi is difficult to pin down because the river channel changes constantly. At Itasca State Park, the official length is determined as 2,552 miles. The U.S. Geologic Survey has published a number of 2,300 miles, the Environmental Protection Agency says it is 2,320 miles long, and the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area maintains its length at 2,350 miles.

Whatever the distance, I intended to see all of it. As I looked at the tiny stream, it was almost impossible to imagine how big it would get.

The Mississippi River’s depth ranges from less than three feet at the headwaters, to the deepest section between Governor Nicholls Wharf and Algiers Point in New Orleans where it is 200 feet deep.

The Mississippi River forms the third largest drainage basin in the world. Its system of 29 locks-and-dams stretches 669 miles between Minneapolis, Minn. and Granite City, Ill., controlling nearly two-thirds of the nation’s watershed.

A raindrop falling into Lake Itasca would arrive at the Gulf of Mexico in about 90 days, but I had no idea how long the trip would take me.

How many times had I dreamed about this? And in about an hour my adventure would start.

Nothing had gone according to plan the day before. With one thing and another, and the inevitable delays that somehow crop up, it was late afternoon before we got on the road. It was about 14 hours from Ames to Lake Itasca, so we drove all night,

By morning, when we arrived, everybody was ready to set up camp and take a long nap. I was running on adrenaline and too much coffee, and couldn’t wait to get started.

Mike came walking up next, with a load of paddles and life jackets.

“We’re here! Just look at this!” I exulted and pointed at the small creek. “The Headwaters! The start of the biggest river in America! Old Man River!”

“Right here,” I gestured around my feet, “Henry Schoolcraft probably stood right here when he discovered this lake and named it.”

Mike was bleary-eyed and seemed unimpressed and ready to fall asleep.

“Mike, look,” I gestured. “When Willard Glasser got right here in 1879, he made a speech and told his men about the important things they were going to do.”

Mike remained apathetic, though he dropped his gear and shuffled over to read the signage.

“I wanna go take a nap somewhere,” Mike grumbled. “Boy, this’ll be fun! First we drive all night, then we paddle all day.”

“Besides,” he added. “There’s not enough water in that dinky little creek to float a canoe. What are we going to do with our stuff? Carry it and wade?”

Mike had a point. At Lake Itasca, the river is between 20-30 feet wide, the narrowest stretch of its entire length and in spots, the channel narrowed to about three feet. At one point, I could sit in the canoe and reach branches on both sides of the river with my outspread arms. In some places, the water wasn’t six inches deep.

The other voyagers came up about then, each laden with various pieces of gear. My sister, Karla Pantenburg, and Al Johnson, a buddy of mine from Ames, were going to travel with us the first week to Lake Winnibigoshish. Andy had come along for no particular reason – he just wanted to see the beginning of the trip.

Everybody agreed with Mike. Since they had no intentions of floating the entire river, they decided to drive about three miles to the next canoe ramp at Wanagan Landing. (Wanagan was named for the floating log kitchen of lumberjacks. The wanagan accompanied the log drives down the river.) The unanimous vote was to pitch the tents and take a long nap, since it was starting to rain.

I was determined to float every foot of the Mississippi if I had to drag my canoe to Wanagan. The back end was ceremoniously dipped in the lake and I got as far as the first log footbridge.

“We have to christen the ship,” Andy said. A U.S. Navy veteran, he was concerned about the correct protocol. He picked up a handful of sand, tossed it inside and said:

“I dub thee Dunderhead!”

“Dunderhead!” I said. “What kind of name is that? Glasser named his canoe ‘Adventurer!'”

“It’s from the German “dunder” meaning foolish, and head, meaning head,” Andy said. “The name comes from ‘Life on the Mississippi!'”

The first few hundred yards of my great adventure were like dragging and shoving a canoe down a wet driveway. There was no room to paddle and I ended up wading most of the way.

Mike and Andy were waiting at the first bridge, and Mike decided to take the other canoe and follow me. After a quick lesson in paddling, he did fine. It didn’t seem like much of a stream, but the Mississippi is so big it has different ecosystems.

The Upper Mississippi is designated as the stretch upstream of Cairo, Ill. From the headwaters, the river flows about 1,250 miles to Cairo, where it is joined by the Ohio River to form the Lower Mississippi.

Based on physical characteristics, according to different authorities on the subject, the Mississippi can be divided into four sections. From the headwaters to the start of navigation at St. Paul, Minn., the Mississippi is a clear, fresh stream that winds through low countryside dotted with lakes and marshes.

The upper Mississippi section extends from St. Paul to the mouth of the Missouri River near St. Louis, Mo. Receiving water from tributaries in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Iowa, the river starts to look like the “Father of Waters.”

Below the Missouri River junction, the middle Mississippi follows a 200-mile course to the mouth of the Ohio River. The turbulent, muddy Missouri, especially when in flood, adds speed to the current as well as lots of silt to the clearer Mississippi.

Beyond the intersection with the Ohio at Cairo, Ill., the Mississippi becomes Old Man River, and it deserves the capital letters in the title. Where these two rivers meet, the Ohio is actually bigger; so below the confluence the Mississippi swells to more than twice the size it is above. Often a mile and a half from bank to bank, the lower Mississippi becomes a brown, lazy river that descends toward the Gulf of Mexico.

That first day was mainly wetlands and pristine pine forests. The overgrown stream meanders around and through some swampy areas filled with cattails and other marsh plants. Beaver dams made the stream a series of small pools.

We didn’t want to hurt the dams with our canoes, but the first one we crossed proved the skill of these original hydro-engineers. It would have taken dynamite to damage it.

After that, when approaching a dam, we’d get at a 90-degree angle, paddle like mad, and try to shove the front of the canoe as far over the structure as possible. Then, before losing momentum, we’d climb up to the front and paddle again.

At every dam, we’d have a contest to see who could get the furthest.

We got to Wanagan about mid-afternoon, and everybody else was already sacked out. Mike climbed into his sleeping bag for a snooze, but I was still too excited to stay still.

I decided to walk back to the Headwaters and take some photos of the sun setting on Lake Itasca. The four-mile hike took over an hour, and I arrived in time to join a group of tourists at the water’s edge.

It was the first time I witnessed a phenomena that occurs wherever the Mississippi flows. About nightfall, people gather on the banks to watch as the sun sets over the water. It doesn’t matter if it is at the Headwaters, at a big city marina or one of those magnificent overlooks where the Old Man flows into the horizon. The river has a magnetic quality at dusk.

I stopped at the Headwaters Inn, the first restaurant along the river, and tried to phone Les. The situation didn’t seem quite real. The fact that I would be on the river for the next two to three months still hadn’t sunk in yet.

But things would seem more natural once I bantered with Les awhile. After the phone rang about 20 times, I hung up, ordered a beer, tried to phone a couple more times, then gave up the idea altogether. Once I left the Inn and started down the road, real fatigue finally caught up with me

I’d been sleepless for about 50 hours and the walk back to camp seemed to take forever. There was no question about sleeping soundly that night!

Click here to read Chapter 3

Leave a Reply