Clamming is one of those river occupations that has changed with the times. Once a thriving business, today clamming is a niche industry practiced by a few on the upper Mississippi.

Prarie du Chein, Wisconsin The SCUBA divers looked like they should be out on the ocean, not in the river channel, somewhere south of Prairie du Chein. They had all the equipment of deep sea divers, including black rubber wet suits, masks and weight belts. They would have looked good in a Jacques Cousteau film, except for the tennis shoes and knee pads.

Whatever they were doing, they looked interesting. As Dunderhead pulled nearer to their boat, I called out:

“Howdy! Are you guys salvage divers? What are you doing with all the diving gear?”

A thick-set, black-clad figure with thick sideburns hollered back.

“We’re diving for clams,” he replied. “We pick them up off the bottom, put them in this barrel and when we get a load, we sell them to a dealer in Prairie du Chien.

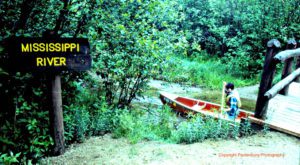

The big river doesn’t look like much as it starts out in northern Minnesota!

“Come on board if you want to. We’re going back down after a smoke and you won’t be in the way.”

Their boat was a specialized rig. It was a flat-bottomed scow with a long arm in the center with a winch attached. A gasoline engine-powered air compressor was rhythmically chugging in the center of the boat. It pumped the air through long hoses for the divers to breathe.

I tied Dunderhead alongside and stepped onto the scow to meet Jim Lessard and Dave Stram, of Prairie du Chein and their air compressor tender, Tod Kramer. The divers lit cigarettes, and took a break while they told me about their jobs.

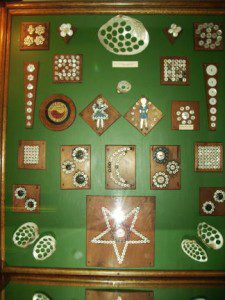

The Indians viewed clams as a food source, and some people still harvest the mollusks to eat. Along the Mississippi, clams were the basis for a thriving pearl button industry.

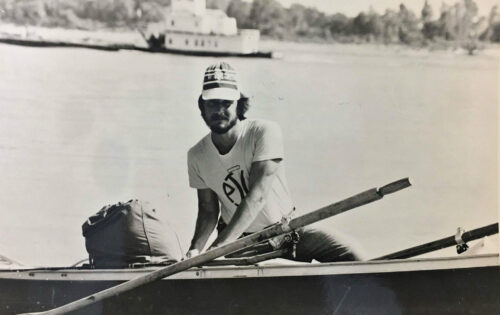

In 1980, I canoed from Lake Itasca, Minnesota to Venice, Louisiana on the Mississippi River.

I’ve found many whole beaches make of shells riddled with button plug holes. The button factories would cut as many plugs as they could out of a shell, then haul the remainder back and dump them in the river.

The area from Prairie du Chein down to Davenport supported many button factories around the turn of the century. Muscatine became known as “The Pearl City” and was the largest manufacturer of fresh-water pearl buttons in the world. In 1898, Iowa turned out over 138,000,000 buttons.

Harvesting the clams was done with dragged sets of hooks along the river bottom:

“It is the habit of the clam to lie with his mouth open upstream, to catch little morsels of food that are carried down… and when one of those wire hooks touches his tender lips, the wretched fool grabs it, closes his shell upon it and holds on…” (History of Muscatine County, 1912)

The clammers then brought in their catch, and threw the clams into big pots of boiling water to kill them. The loosened shells were pried apart and the whitish meat was cleaned out. The shells were hauled to the factory, where they were soaked in water for about a week. This softened the shells so they wouldn’t break while being sawed. Button factory workers made good money, between $4 and $10 per week.

In 1891, Boepple Button Company opened a one-room factory in Muscatine, where the supply of mussels was good. By the next year the company was doing so well that it moved to a larger building, where it operated for four years. 1891 marked the beginning of the river button boom, and like most other Mississippi River businesses based on natural resources, there was no attempt to regulate the harvest.

The big river is a tiny creek at the headwaters. This is the first bridge on the Mississippi.

The factories cut, polished and sold pearl buttons as fast as the clammers could bring in the shells. By 1900, there were very few clams left in the Mississippi, but clam fishers found new, untouched beds in the Arkansas, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers.

The shells were shipped by barge or rail to Muscatine, and the button business kept going. But manufacturers eventually turned to plastics, which were cheaper and easier to work with. Button making all but disappeared from Iowa.

When the Mississippi clam beds had been fished out, the federal government started a clam and mussel hatchery near Fairport. The hatchery hoped to produce enough mussels to restock the riverbeds. Unfortunately, rivers became polluted with industrial waste and city sewage and the mussels couldn’t survive in the polluted water.

Today, Lessard told me, the shells are shipped to Japan, to be used in the pearl industry.

“When the Communists took over China, the Japanese searched the free world for shells to replace the ones they used to get from the Yangtze River,” he said. “The ones with the right degree of hardness are found in the Mississippi.”

Once harvested, the shells are cut into dice and tumbled in sand and pumice until they round into spheres. Then they are inserted into oysters. The oysters coat the irritants with nacre to form pearls.

“It takes about a ton of clams to produce 25 pounds of those slugs,” Lessard said. “The shells are boiled clean and the meat is sold to commercial fishermen. We get $160 a ton at Prairie du Chein.”

Once clams are located, there are usually enough to keep the clammers busy.

“Because of the current, the clams are found in veins parallel to the channel,” Lessard said. “A good vein can keep us busy for a couple of days, providing another clamming boat doesn’t see us and start on the other end!”

The ideal depth to work in is about 12 to 15 feet, he said, though they sometimes go as far down as 40 feet when they find a particularly good vein. The pressure of the deeper water tires them out faster, and if they have to surface quickly, there is that much further to go. The muddy water has no visibility, causing the divers to work in pitch blackness.

“We wear the knee pads and tennis shoes to protect us when we’re crawling around on the bottom,” Lessard said. “We can’t see anything, and we have to feel around for the clams.”

Their cigarettes were down to butts, so the divers started putting on all their gear. Kramer hoisted up a weight belt, and Lessard shrugged his way into it.

“It takes 35 pounds of lead to hold us on the bottom in this current,” Lessard said. “There’s no problem getting down there, but getting back up is something else!”

The clams were put into a sawed-off, 50-gallon steel barrel with hooks welded on to attach it to the rope. When it was filled, the divers would surface and unload it.

“If we get into trouble down there, Tod hauls us up by the ropes attached to the air hoses,” Lessard said.

The barrel was tossed overboard and divers followed. While the divers are underwater, Kramer keeps one eye on the air compressor and one eye on the bubbles that mark the diverse locations. There is no elaborate signaling system – if the bubbles act funny, Kramer hauls on the rope. He also sizes the clams, throwing the smaller ones overboard. I waited for about 20 minutes until Stram and Lessard filled the barrel and came up for another breather.

On a good day, they’d harvest about 5,000 pounds, which would fill the boat to the gunnels. By the time they sold the meat and the shells, they would have made a pretty good day’s pay.

I asked them about the big catfish story that is told at every lock and dam, and if they thought there was any truth to it. (I heard that story all the way down the river. At the lock-and-dam or bridge just down the river, the story goes, divers had had to go down and repair something. They found catfish laying on the bottom as big as sharks. The divers all emerged shaken, and swore they would never go down there again.)

Stram and Lessard looked at each other and grinned.

“We never know what we’ll run into down there. We’ve found shotguns, anchors, junk – that sort of thing. Never found anything valuable except the clams,” Lessard commented. “As far as a catfish as big as a shark or a whale, well, I don’t know anything about that!”

The inherent danger was just part of the job. Personally, the thought of picking clams up clams, in pitch darkness, in the river current on the river bottom gave me claustrophobia.

“I suppose it could be dangerous if you weren’t careful,” Lessard said. “The big disadvantage, though, is that I feel like a prune after being in the water all day!”

I laughed and shoved off for downstream. I never got bored on the river!

To read the other chapters of “Downriver: A Mississippi River Canoe Voyage, click on Mississippi River canoe trip.

Please click here to check out and subscribe to the SurvivalCommonSense.com YouTube channel – thanks!

Leave a Reply