We were ready for a break at Little Falls. While camping along the river was great, there are times when a break in town was welcome. Specifically, Mike and I looked for a good hamburger, a big ice cream cone, and a movie. Or several.

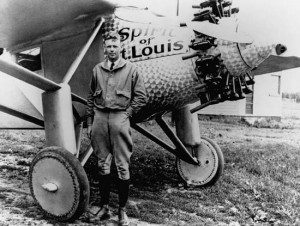

Little Falls was the boyhood home of Charles Lindbergh, the first pilot to fly solo from New York to Paris.

Little Falls is near the geographic center of the state. Established in 1848, it is one of the oldest cities in Minnesota. The area has always been well-traveled by different peoples. The Dakota Sioux used the Mississippi as a primary transportation route, and camped along its banks

The Red River Oxcart Trail, an important route for settlers, passed on the east side of the river. The segment was part of the Woods Trail, which stretched from St. Paul to Pembina, North Dakota. Little Falls was a trading post along the trail.

The town was named after falls that were located on the Mississippi, which travels through town. Several attempts to build dams over the falls took place throughout the town’s history, some of which powered saw mills in the nineteenth century. Today, the Little Falls Dam serves as a hydroelectric station that generates power for the surrounding area.

But my interest was in a famous former resident and one of my personal heroes: Charles A. Lindbergh.

Lindbergh, an American aviator, made the first solo nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean on May 20-21, 1927. Lindbergh’s feat gained him immediate, international fame. The press named him “Lucky Lindy” and the “Lone Eagle.” The shy, slim young man was idolized and showered with honors.

But it was what he did with that fame that made him a hero. Lindbergh mentioned in one of his books that he was

besieged with endorsement offers and financial opportunities that would have made him a wealthy man. But he decided early on that money was not the prime motivator for him, and Lindbergh went on to become a great man.

Lindbergh invented an “artificial heart” between 1931 and 1935, a device that could pump the substances necessary for life throughout the tissues of an organ.

In 1953, Lindbergh published “The Spirit of St. Louis,” an expanded account of his 1927 transatlantic flight. The book won a Pulitzer Prize in 1954.

We set up camp at Charles A. Lindbergh State Park, a 436-acre state park on the outskirts of Little Falls along the Mississippi. The park was once the farm and summer home of Lindbergh. Their restored 1906 house and two other farm buildings are within the park boundaries.

The Lindbergh house contains many of the family’s mementos. The Lindbergh Visitor Center is near the home and showcases the lives and careers of three generations of Lindberghs in Minnesota.

After touring the Lindbergh home and the visitor center, Mike and I walked into town to take in a movie. We saw “The Long Riders,” a story about Jesse and Frank James and their association with the Younger Gang. The movie remains one of my all-time favorite westerns.

Sometimes, Mike must have thought we’d never get to Minneapolis and Saint Paul. For five weeks, he’d steered the canoe, ate like a lumberjack three times a day, and wondered how much further it was to our sister Linda Spring’s house in St. Paul.

Finally, I taught him how to read the river charts. Then, every night, he’d chart the day’s progress and figure out how much further we had to go.

Mike’s last night on the river was pretty typical. We were lucky enough to get a ride around the Coon Rapids dam, and we camped on an island in the middle of the river. (Here’s what the dam looks like today!)

A yellowish glow downriver marked Minneapolis, but there were only the sounds of nature where we were. A beaver swam around in the water and slapped his tail when he saw us. A few mosquitoes buzzed around. The quiet rushing of the water created a soothing backdrop.

With supper over, I rigged my fishing rod and waded out into the water to try catching a few walleyes for breakfast. Mike had gathered enough wood for a bright fire, and had dug “Huckleberry Finn” out of his bucket. He draped his insulite sleeping pad over the bucket to form a recliner near the light. When he leaned back and started reading, he looked like some sort of a Courier and Ives etching.

I fished for about half an hour before deciding the fish were not biting nearly as much as the mosquitoes. Mike looked up when I waded in. I sat the rod down by the canoe and hunkered down by the fire.

“You sure we’re gonna be in Minneapolis tomorrow?” he asked and gestured downriver. “This place doesn’t look like a city!”

“I figure we’ll be in St. Paul by mid-afternoon, phone Linda and (brother-in-law) Randy, and be eating supper at their house by about six o’clock.”

“Great! I thought we’d never get here!” he said and went back to reading.

“Yeah, you did all right,” I commented, “Tomorrow night it’s all over. In a couple of days, you’ll be home with all sorts of stories to tell your buddies.”

Mike grunted and turned the page. He’d about finished the book.

“How are you going to handle the canoe without me to steer it?” he asked.

“Randy told me over the phone that the Grumman rowing rig had come in the mail, and all I have to do is get some oars,” I said. “The river gets a lot wider, and everything should be OK,”

“Yeah, you’re going to have to set the tent up by yourself and find firewood, and everything else, too,”

That had been Mike’s job for the last five weeks. As soon as we stopped for the night, he’d set up the tent, rummage through the underbrush finding sticks, then start the fire. He’s gotten really good at it, too.

While Mike was setting up camp, I usually cleaned fish, and fired up the stove. By the time the tent was set up, the hot chocolate was finished and Mike would sit and watch me cook while he sipped his drink. We had gotten our routine down to a science. From the time we pulled into a camping site to getting the camp completely set up took about 15 to 20 minutes.

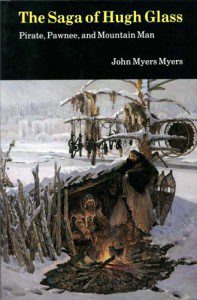

The fire and the river sometimes brought out a story. Tales of the mountain men during the fur trade era and the French-Canadian voyagers particularly interested Mike. His favorite yarn was about Hugh Glass and the grizzly.

Hugh Glass had the epitome of a survival mindset! Badly wounded by a bear, he still managed to crawl nearly 200 miles to safety!

Hugh Glass was a Rocky Mountain fur trader. In 1823, he joined with Ashley and Henry’s second fur brigade to the upper Missouri River country. Glass and a partner were out hunting for meat when they startled a sow grizzly bear with two yearling cubs.

Although the two mountain men were able to handle the grizzlies, Glass was severely injured in the attack, receiving deep lacerations and puncture wounds to his scalp, face, chest, back, shoulder, arm, hand and thigh. Glass, clearly, was going to die, but he made it until the next morning.

Henry’s party was at that time passing through dangerous Indian country. Henry couldn’t jeopardize the safety of the entire party for one man, so he sought two volunteers, with an incentive of six months pay, to remain behind with Glass until he should die.

Jim Bridger, at only 17 and on his first trip to the mountains, and a man named John Fitzgerald volunteered. Finally after a week, Hugh Glass was still alive, but showing no sign of improvement. Bridger and Fitzgerald lost their nerve, packed and left, taking Glass’s gun and gear.

Glass, however, did not die. Sometime after he was abandoned, Glass came out of his coma, so weak he could only crawl. Then began Glass’s six-week ordeal of strength, determination, luck and fortitude. He lived on carrion and rattlesnakes as he dragged himself back to Fort Kiowa, a trading post almost 200 miles away.

So I’d retell parts of this story whenever we had a tough portage or lengthy paddle into the wind.

Bedtime came early on the river. A day of paddling, followed by a full meal, made the sleeping bags seem luxurious.

I kinda wondered if the Hugh Glass story had somehow inspired Mike. Mike wasn’t overly concerned about the accommodations anymore. He could sleep anywhere, and didn’t even bother to wake up when the lightning cracked and it started to rain. He’d quit complaining about three weeks ago, and even when Mike was sweating at his paddle, or humping over a portage, his attitude was one of grim tenacity.

He was a full partner in the whole trip, and pulled his weight like someone much older and more experienced. I was touched by his concern.

“OK, Mike, you’ve convinced me. I’ll have a hard time getting along without you,” I said. “You can stay another month and get out in Davenport, Iowa.”

“Oh, no you don’t,” Mike burst out. “I said I’d go as far as Linda and Randy’s and I have and I quit tomorrow! You couldn’t pay me to go any further!”

I was still laughing when he got up, put away his book and unrolled his sleeping bag. I sat by the fire a while longer and then went inside the tent. There’s something about a fire along the river…

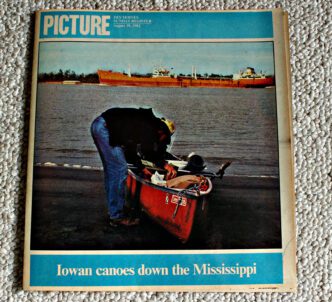

We were up at dawn and on the river shortly afterward. Within an hour we hit the city limits and in another mile the commercial part of the Mississippi started.

Within a few miles, and virtually overnight, the river changed from a semi-wilderness stream to a commercial river.

Towboats – the first we’d seen – moved loads back and forth in the channel and stirred up the water. The docks came into view then, followed by the bridges and the noise of rush hour traffic. The tall buildings in downtown Minneapolis looked incredibly high from water level.

At St. Anthony Falls, we came to the first lock-and-dam on the river. The Mississippi’s lock-and-dam system is what keeps the river navigable. About every 30 to 40 miles below St. Paul, a dam backs up the river, forms a pool and keeps the channel deep enough for barges.

The idea of traveling north of St. Anthony Falls on the Mississippi was made possible when Congress approved the Upper Minneapolis Harbor Development Project in 1937. This project, according to the Minneapolis branch of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, included the construction of the Upper St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam that was completed in 1963.

With a lift of 49 feet, the lock at St. Anthony Falls accounts for more than 10% of the total height change of the Mississippi River between the Twin Cities and St. Louis, MO.

This Lock and Dam along with the Lower St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam allow navigation to the head of the Mississippi River’s 9-foot channel and spans the remnants of the Mississippi River’s only waterfall.

We found out that a single canoe can pass through a lock and dam; and it’s free!

To get past the dams, a lock is installed. It looks like a giant box, with swinging doors on each end and is filled and emptied with huge pumps. If you’re going downstream, for example, the lock is filled to the level of the upstream channel. Then the boat is driven into the lock, the doors are shut and the water is lowered, which drops the boat down. The process is reversed for going the other way.

The lockmaster at St. Anthony Falls sent us through alone. By the time we dropped the 50 or so feet to the next level, Dunderhead felt like a pea in a shoe box.

Mike and I each held the end of a long rope and the canoe was slowly lowered with the water level. A lock employee watched the whole process. Except for the increased boat traffic, the rest of the way through the Twin Cities was uneventful. Finding a place to land, though, was quite a chore since all the riverfront property was either private or had steep banks or no access for a car.

Finally, we landed at Lilydale Marina below St. Paul. I walked up to the lounge, phoned my brother-in-law, bought a cold beer and a Coke and went back to the dock. Mike was already hauling gear up out of the water and stacking it under a shade tree.

Together we pulled the canoe up under the tree, turned it over and sat down to open our drinks.

“You remember when you kept yelling at me for banging my paddle against the side of the canoe?” Mike asked.

“Sure. That was after you kept getting slivers in your hand because you were busting up your paddle,” I answered. “At the rate you were going, you’d have worn it out.”

“You remember what else?” Mike got up and picked up his paddle. “You said once we got to St. Paul, you didn’t care if I broke it!”

Mike wound up and smacked the paddle across the tree trunk. It broke neatly in half. I stared, then laughed.

“Hey, that paddle cost me 10 bucks! Now I’ve got to replace it!”

Mike held up both pieces and chortled.

“Yup, but I’m done paddling, and I’m not gonna use it again, and nobody else is either,” he said. “And you can’t beat me up because I’ll tell Mom and here comes Randy!”

Randy and Linda pulled into the little park in their Bronco. Randy and I lifted the canoe up on the roof while Mike told Linda stories about the river.

Randy commented how different Mike looked, and for the first time, I realized the impact the river can have on people,

Mike acted like a confident young man, in everything he did, from hauling gear, paddling, to the way he walked. The pale, pudgy kid who’d left Lake Itasca five weeks before had dropped 20 pounds and now had a dark tan, and hardened muscles from all the paddling. The high protein diet had really helped – he’d slimmed down a lot and had well-defined chest and arm muscles.

There was also a new confidence that comes from succeeding at a difficult task. Mike was jubilant about the end of the trip and chattered about what he was going to do at home and the things he was going to eat. I planned on visiting Linda and Randy for a couple of days, then getting back to the river. But Mike had one last request.

“Wherever you decide to stop, you have to break your paddle too,” he said. “It shows the trip is over.”

I promised.

Leave a Reply