Funny how things work out. Sometimes an experience will bring up memories that have lain dormant for years. Maybe the memory didn’t seem particularly important at the time it was happening. Possibly the new experience is like a key word on a computer that opens up an apparently unrelated, or unsuspected file. Or maybe that first memory wasn’t complete, without something to trigger it.

Beats me. That night, on a Mississippi River sandbar I sat next to a dying campfire. My thoughts were about another

Omaha encampment, late 1800s. In 1780, the tribe numbered almost 3,000. By 1802, the population had declined to about 300 because of sickness and warfare. (Omaha Public Library photo)

campfire on the Omaha Indian Reservation, three years before. (This story will be in context, and make more sense, if you read “Downriver Chapter 10, Amos Owen, Dakota Holy Man” first!)

The rhythmic thump-thump-thump of the drums had been going on for hours, accompanied by the high falsetto chanting of the Native American Church’s funeral services.

It was kind of chilly, in the damp pre-dawn light, and I was tired from staying up all night. A good friend of mine, Hiram Tobacco, had been killed in a car accident. My VISTA (Volunteers In Service To America) partner, John Deakyne, of Gosport, Indiana, and I had been invited to the funeral services.

The obsequies were something an Iowa farm boy could only imagine. The campfire inside the tepee made it glow like a yellow, cone-like paper lantern. The singers were vague, shadowy silhouettes against the walls. The figures swayed back and forth as they passed the drum around the circle and joined in the choruses of the ceremonial songs.

Most of the participants had eaten peyote buttons or drank the bitter tea made from the herb. Peyote is a natural hallucinogen, and members of the Native American Church of America believe that while under the influence of peyote, in the church service, they communicate directly with the creator.

Inside the house, Hiram’s body was lying in state. John had gone inside to sit beside the casket for awhile. Other people would come to the edge of the firelight and gather quietly or go back inside to sit with the body. Over everything hung a somber, reverent air. I sat on the damp grass, fascinated in spite of sleep deprivation.

A low, hostile growl interrupted my thoughts.

“Hey, white boy!” came a harsh, guttural voice from behind me. “What do you think you’re doing here?”

Startled, I snapped my head around to see a husky figure behind me. John and I had been personally invited to the services, which was a great honor. But maybe there was somebody who didn’t want us there.

A twinkle in his eye showed harassment was planned. It was Joe Harlan, one of my best friends.

“Sit down,” I ordered in my best Lone-Ranger-to-Tonto voice, and Joe stretched out on the grass beside me. Joe worked at the Macy Alcohol Counseling Center treatment center with John and me. Joe had gone off to college, then returned to work with his people. He was a devout Mormon, a confirmed family man, and one of the best people I’ve ever met.

During slack times at the center we discussed everything, including philosophy and psychology. The existentialist school of psychology had particularly impressed Joe.

Rodney Grant s a famous Omaha. He starred as “Wind In His Hair’ in the 1990 movie “Dances With Wolves,” and as Crazy Horse in the TV movie “Son of the Morning Star.”

The drumming and singing came to a crescendo, then stopped while the drum was passed on. The night wasquiet and still, and I could hear crickets while everyone waited for another song to start. We sat in silence, smelling the wood smoke and wet grass, looking at the tepee and listening to the night noises, while our minds were elsewhere.

The music started again and I found myself swaying to the beat, though I hadn’t the faintest idea what the song meant. Joe snapped me out of my reverie.

“About Carl Jung’s theory, the Great Dream,” Joe said. “That idea has been on my mind lately. Tell me what you think the Great Dream is.”

I thought a moment.

“The Great Dream means, that at some time everybody has a great dream or vision that will change that person’s life, provided the dream is understood,” I said. “That’s close, anyway.”

“I’ve been thinking about that. The Great Dream is similar to what some of the Indian people do,” Joe paused a moment, trying to find a common meaning. “I guess you’d call it some sort of vision quest.”

I laughed.

“Vision quest?” I snorted. “I think I’ve read a science-fiction novel with that title! Vision Quest! Or maybe it was a movie!”

Joe shrugged apologetically and grinned.

“I know, I know, but what else shall I call it?” he asked.

Joe was referring to a ritual that was ancient before Columbus landed in America. A few young natives still go through a four-day period of prayer, fasting and meditation out in the woods somewhere. During that time, they look for their vision. When the thing is over, they come back with an idea of what path their life will take.

I’d heard about idea before. At the time, a “vision quest” seemed like something the Indians came up with to mystify whites. The idea was interesting, but the practice seemed odd, and appeared to have died out.

“People have lost the feeling they should get from being associated with nature,” Joe stated. “Today, people think they should learn everything from books or television. They ignore the things they already know.”

“What?” I asked. The comment had gone over my head.

Silence for a while as we watched the sky lighten in the east. Joe tried another approach.

“Many people could get their acts together, and live much more happily if they would go into the wilderness and let the peacefulness seep into them,” he said. “Then, they have a chance to learn the things that are deep inside them.”

Joe had lost me again. I told him that.

“Look, you should go out sometime on a vision quest and try to find your Great Dream,” he said.

From my perspective Joe was talking in circles. And he was crazy to suggest I do something as ridiculous-sounding as a Vision Quest. Hanging around the woods, with nothing to eat, getting chewed on by mosquitoes seemed stupid.

“Joe, I just went backpacking in Idaho this summer. I’ve been out in the mountains of Yellowstone, alone, for 14 days straight. I only saw a couple people the whole time. I hiked the 225 miles of the John Muir Trail in California, and was on my own for another 14 days. There were no great, enlightening revelations from being alone in the outdoors,” I said. “And I still hang out in the woods, hunting and fishing, more than just about anybody I know.”

“But you see nature as an adversary,” he replied. “You go out and climb mountains, or walk long distances because you have to conquer or prove something. You should go with the idea of just being there. You should go look for your vision.”

The whole concept seemed ridiculous.

“No way! Sitting around in the woods, waiting for inspiration to hit me! What would I tell people if they asked what I did on my summer vacation?” I laughed out loud, forgetting momentarily where I was.

Joe frowned.

“There is another type of meditation some Indians used to practice,” he said. “You take a long walk or journey. You try to see and feel things with your whole being. You concentrate on where you are and don’t pay any attention to anything but the present. You start to feel a natural peace…”

“Like the aborigines in Australia,” I interrupted. “They call it ‘walkabout’ or something like that. They take these long walks, and concentrate on where they are, and what they are seeing right then. They claim they tune in and let the places call to them, and direct the journey.”

Joe looked at me intently, like maybe I was on the verge of understanding something important.

“So, if I was going to do something like that, I’d do a Hike About, because I’d want to take along a tent and sleeping bag and enough gear to be comfortable!”

I laughed and Joe rolled his eyes, like he felt he was wasting his time. But Joe was being serious and I was punch-drunk from lack of sleep.

“Joe, there’s nothing I enjoy more than an early morning walk through the woods,” I said. “I’d much rather be out hiking than watching the football games on Sunday afternoons …”

Joe held up his hand to shut me up. He shook his head in a pitying sort of way. Our cultural backgrounds couldn’t find a bridge. Not yet.

“Look, you’ve said yourself that you’re just kind of wandering. You don’t know what you want to do, and all you’ve figured out is what you don’t want to do,” Joe said. “There’s nothing for you here on the rez, but you’re talking about staying when VISTA is over. You don’t have a clue about what comes next.”

We sat in silence for awhile as we listened to the coming of the dawn. The crickets quieted down, and the horizon lightened. The leaves on the tree above us started to change colors, from black, to dark green to green. The light, barely visable at first, brightened by the minute and the yellow disk of sun started to be seen on the horizon. Some of the women were building a fire away from the tipi to cook breakfast for all the participants. I started to nod off.

“You will know you have been on a vision quest when you get done with it,” Joe said finally. He changed the subject.

That night had been almost forgotten, because it didn’t make sense and I never did figure out what Joe meant. And it was odd that memory should come up then.

The Mississippi flowed in the moonlight, and I looked across to where the other shore was vaguely visible.

Well, what the hell, maybe I should try a vision quest sometime. I appeared to be at some kind of a crossroads and things sure hadn’t worked out for graduate school. And this river trip was already a lot different that I originally though it would be.

Maybe I should have stayed longer and asked Amos if he knew what Joe had been talking about. Maybe I should go back and see if I could participate in a sweat lodge ceremony at Amos’.

“Or maybe I should go to bed!” I kicked sand over the coals, and got my sleeping bag out of the bucket. The sound of the river put me to sleep.

(Editor’s Note: In 2006, I made a special trip to visit the Omaha Reservation. I looked up several friends from my VISTA days. I found Joe Harlan mowing the lawn of his church. After visiting for an hour of so in the shade of a tree, I brought up the night of Hiram’s funeral. To my surprise, Joe remembered our conversation, too. Joe asked if I ever did anything with that vision quest idea. Joe passed away in 2021.)

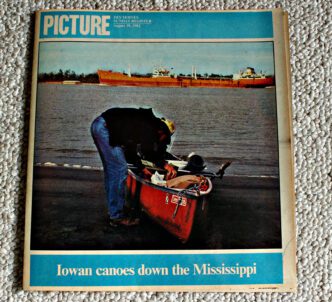

To read the rest of “Downriver: A Mississippi River Canoe Voyage” click here!

Leave a Reply