Redwing, MN has a large marina, beautifully restored old homes and a great local museum. From the marina, I wandered up to the Goodhue County Museum on the hill. In the early 1850s, settlers came to Redwing to farm in Goodhue County. Land was selling for $15 per acre, and the cash crop was wheat. A few bumper crop years could pay the cost of the land.

Once the railroads connected southern Minnesota with Minneapolis and Saint Anthony, where the largest flour mills were built, the port at Red Wing lost prominence. In the last half of the 20th century, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built locks and dams and deepened the river channel. This reinvigorated river traffic for shipping grain and coal.

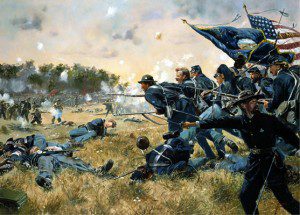

Redwing was also important in Civil War history. Goodhue County supplied most of the men for the famed 1st

Minnesota Volunteer Infantry. On July 2, 1863, the second day of fighting at Gettysburg, the regiment prevented the confederates from pushing the federals off Cemetery Ridge, a crucial position in the battle.

The regiment was ordered to assault a much larger enemy force to buy the time needed to bring up reinforcements. During the charge, 215 members of the 262 men who were present became casualties. The 83 percent casualty rate is the largest loss by any surviving military unit in American history during any single engagement.

Despite the incredible losses, the 1st Minnesota fought the next day, helping to repulse Pickett’s Charge.

Area patriotic parades were noticeably shy of participants after the war, the museum curator told me, because there simply were not many veterans.

There were other interesting exhibits. One display featured a beautiful red pipe bowl made by a local craftsman named Amos Owen, a Dakota Sioux Indian. A little more research, and I found what George Catlin wrote about the pipes in the early 1800s:

“Pipes among the American Indians are not only matters of luxury, where they are always emblems of peace and tendered as friendly salutations; but are kept in all tribes by the chiefs as instruments for solemnizing treaties; in which case they are public property; considered sacred and denominated ‘calumets’ or pipes of peace.” (George Catlin, “Indian Art in Pipestone,” Smithsonian Institution Press, City of Washington, 1979).

The museum people told me more about Owen, and I decided to see if a visit and interview was possible.

Over the phone he told me to “C’mon out!”

Owen and his wife live in a neat white frame house near Welch, MN, within sight of the Prairie Island Nuclear Power plant.

Upon arrival, I saw a stocky man in a flannel shirt and jeans, working on a picnic table. He had a full array of modern files and tools, and was shaping a piece of red stone. He put down the file, wiped the stone dust off his hand onto his pants leg, and extended it to me with a smile.

“Hi,” he said. “I’m Amos.”

We shook hands.

“Why didn’t I bring tobacco?” I thought suddenly. The traditional way to greet a holy man or a spiritual leader, I knew from my VISTA hitch on the Omaha Indian Reservation, was to present him with some tobacco. The usual gift is a sack of Bull Durham.

But amenities didn’t matter. I got the impression almost immediately that Amos treated everyone the same. Amos looks like someone you’d want to hang out with. He has a firm handshake, a quick smile and a gentle-looking face. Deep smile lines on each side of his mouth show the man laughs a lot. His clear eyes are deep brown and friendly. A full-blood Dakota Sioux, his hair was worn long in a pony tail, and the gray hairs were just starting to outnumber the black. Except for his glasses, Amos, 68, had the classic warrior look that was used as the portrait model for the nickel.

Amos is a model for a lot of things. Because of him, a bit of Native American culture survives in the

shadow of a nuclear power plant. Sometimes, the sound of drums, singing and chanting in Dakota Sioux language can be heard as people worship in the sweat lodge in his backyard.

There is no written Bible in the Native American religion and no ordained ministers. People find the spiritual leaders though, and Owen gets visitors from all over the world. Many visit and participate in a worship service in his sweat lodge.

Amos has had a lifelong involvement in the Indian religion. To him, like his forefathers, religion is not just something for Sunday morning.

Over coffee in his kitchen, Amos told me about himself. He was reared in the Welch area and hunted, fished and played along the banks of the Mississippi. When he reached manhood, he became a farmer and never intended to leave his beloved river valley. Except for time away in the military, Amos has lived in his present house since 1938.

Amos a good interviewer, too. My attempt to interview this revered holy man ended up as a very enjoyable bull session that went on most of the afternoon. We talked and laughed about all sorts of things, and Amos was fascinated with my river trip. In fact, it was hard to interview him because of his interest in me!

There was a glint of approval in his eyes when I explained why the river trip had to be a solo. Turns out, we knew some of the same people on the Omaha Reservation, and he was really interested in my perceptions of the Indian culture. It partially explained my interest in the ceremonial pipes.

Pipestone, MN, is the only location in the United States where a unique red sandstone can be found. Native Americans have always gone there to gather the stone to make sacred objects.

At first, pipe making was just a hobby for Amos. He gave away most of those he made, and then, only to people who would use them for ceremonial purposes.

His peaceful lifestyle was changed in 1941 by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Shortly after war was declared, Amos and his two brothers enlisted in the armed forces. His brothers eventually became career military men, and Amos planned on staying in the Army when the war was over.

In 1945, Owen was stationed in the Philippines. A dawn attack by Japanese tanks and infantry ended any hopes for a military career. During the battle, Amos was severely wounded. Amos spent the next 11 months in hospitals before being honorably discharged as a 100-percent disabled veteran. He went home to recover.

“I went back to making pipes because for a long time that was about all I was able to do,” he said.

While recovering from his wounds, Amos became more and more involved in studying the Indian culture.

“During the mid-1800s, the Christian missionaries on reservations managed to get the Indian religion banned,” he said. “After the Ghost Dance uprising in the late 1800s, the religion was outlawed for many years.”

The religion never died out, though. After years of self-disciplined study and meditation, Amos became a spiritual leader.

There was no formal ordination, public recognition or anything like that. People somehow found their way to visit Amos and began asking advice and counsel. Gradually Amos found himself in the position of being a full-time mentor to many people.

In the meantime, his stonework steadily improved.

Amos’ pipes are all over the United States and in many European countries, but they are only sold for ceremonial purposes. The pipes have also made Amos an international figure. Explorer Jacques Cousteau stopped to visit Amos, during Cousteau’s Mississippi River voyage.

And other Europeans know about Amos. Several years prior, Amos was invited to a crafts fair in Budapest, Hungary, to demonstrate his pipe-making skill. He found himself a center of attention.

“The Hungarians are very friendly people,” Amos said. “The hobbyists swarmed all over me when the exhibit was over. Sometimes they followed me back to my hotel.”

In Budapest, he found a group of Europeans – complete with tepees – trying to live according to Native American traditions and teachings. They asked Amos to visit their community and he soon became their spiritual leader. Amos made them a pipe.

“That pipe was blessed in three languages -English, Hungarian and Dakota Sioux,” he said. “The group still stays in touch with me and still celebrates May 20 as the day of the black stone pipe ceremony.”

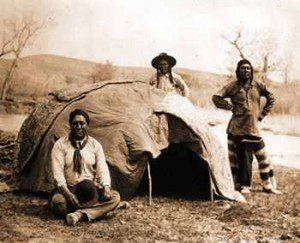

We walked out into Amos’ back yard to a mound of various-colored coverings, which covered his sweat lodge. Quilts, sleeping bags and blankets insulate the lodge and the top is sometimes covered with a tarp or piece of plastic to keep rain from soaking in.

He pointed.

“The sweat lodge is the oldest way to pray on the North American continent,” Amos explained. “People from all religions come here to worship.”

In the Dakota religion, a sweat lodge and purification rites are an essential part of the prayer service. Any place that gets hot enough can serve as the site for a sweat.

Amos’ lodge is heated with hot rocks, and steam is caused by pouring water on them. Outside the lodge, a large pile of fire-blackened and cracked rocks attest to the number of sweats that have been held inside. The lodge traditionally faces the east. Ironically, the cooling tower of the power plant can be seen from the west side.

Owen gestured toward the tower.

“That’s one reason I pray a lot!” he chuckled.

Like smoking the ceremonial pipe, a sweat lodge ceremony is something to be done with other people. Participants in

the purification rites crowd inside the lodge and several rocks are heated and put into the pit in the center. For about two hours, they pray and meditate. There are no formal prayers, and people of different beliefs worship side-by-side.

One of our connecting points was reservation drug problems. Amos was curious about my perspective on alcohol and drug problems among the young people.

“I’ve seen enough to know I don’t know much,” I commented. “There’s no simple answer. But a major contributor is the lack of role modeling and mentoring for the young people.”

Amos nodded. I mentioned how hard it was to find adults on the rez who managed to stay drug-free and productive.

“The kids see no hope for the future, and they look at the adults in their community and they rarely see people who are doing well,” I commented. “They have no vision for their futures, because they can’t see beyond the rez.”

Amos knew what I was talking about.

Sometimes, people come to Amos for help with their “vision quest”. I didn’t really understand the concept. But essentially, it appeared to be an attempt to become one with nature (or something along those lines). The person on the quest, after few days of fasting, prayer and meditation, has a dream or vision of what direction his life journey will take.

“A lot of people, especially the Indian people, come here to get started on a new way of life,” Amos said. “The purification rites and prayers seem to give them the strength to live the right way.”

“And just what is the right way?” I asked.

All the sudden, I knew what he would say. I’d heard the answer years before I heard the question. It was on the Omaha Indian Reservation, in Macy, Nebraska, in a surprisingly similar situation when I was talking with another Indian who was on his way to becoming a holy man.

“You know the right way,” Owen said. “Everybody knows. They just have to listen to what they know.”

He laughed, and for a moment, the non-stop conversation that had gone on for several hours stopped. There was a silence between us. I really wanted to stay and participate in a sweat that night. Amos looked at me expectantly, apparently waiting for me to ask for a sweat lodge ceremony. It was evident he’d welcome the idea.

But, I was a long way from the river, had quite a distance to go before stopping that night, and had to get going. Reluctantly, I left.

Amos walked me to the end of his driveway, and waved as I headed back toward town. I promised to send him a postcard.

To read the rest of “Downriver: A Mississippi River Canoe Voyage” click here!

Leave a Reply