From Cass Lake to Grand Rapids, Mike and I paddled through the land of Paul Bunyon, the legendary logger, on the river that was the highway of the Minnesota timber industry until the 1940s.

The world’s largest animated man, according to theme park hype, is this display of Paul Bunyon in Brainerd.

Local legends are part of the fun of traveling the Mississippi, and Paul Bunyon is one of those yarns that just get bigger in the telling. He is a larger-than-life fictional folk hero who is a symbol of strength, an admirable work ethic, and the resolve to overcome all obstacles. Paul Bunyan is part of the western tall tale literature, which often populates the landscape with beings of gigantic proportions.

Mike and I went to the Paul Bunyan Center while we were in Brainerd, and the tourist attraction was enjoyable and a nice break from paddling.

Paul Bunyon is known mainly for large stuff. Along with his faithful companion, Babe the Blue Ox, the two take on mosquitoes of tremendous proportions, rainstorms that last for months, and natural obstructions like mountains ranges in their stride. The legend was popularized by newspapermen across the country in 1910 and has been a part of the American culture ever since.

One of my favorite tales was about the winter it was so cold that all the geese flew backward and all the fish moved south and even the snow turned blue. Late at night, it got so frigid that all spoken words froze solid before they could be heard. People had to wait until sunup to find out what folks were talking about the night before.

Originally Ojibwa land, Brainerd was “discovered” on Christmas Day in 1805, when Zebulon Pike stopped there while searching for the Mississippi headwaters. Crow Wing Village, a fur and logging community near Fort Ripley, brought settlers to the area in the mid-1800s.

All the towns in that area base much of their economy on lumber. Brainerd was the brainchild of Northern Pacific railroad president John Gregory Smith, who in 1870, named the township after his daughter, Anne Eliza Brainerd Smith, and father-in-law, Lawrence Brainerd.

The railroad company built a bridge over the Mississippi seven miles north of Crow Wing Village and used the Brainerd station as a machine and car shop, prompting many to move north and abandon Crow Wing. Brainerd was organized as a city in 1873.

We didn’t stay long in Brainerd, because I wanted to find a real old-time logger, and people in Brainerd recommended looking at the Grand Rapids logging museum a few miles further south. The banks of the river between the two towns are lined with trees, most of them second and third growth white pines.

Grand Rapids was originally founded as a logging town, as the Mississippi provided the optimal method of log shipment to population centers. The Mesabi Range or Iron Range region of Minnesota begins with mines north and northeast of the city. Although technically part the Iron Range, Grand Rapids and its economy has been historically based on paper manufacturing and other wood products.

Grand Rapids’ other claim to fame is being the birthplace of Frances Ethel Gumm, who later became legendary singer

and actress Judy Garland. A local museum is dedicated to her life and career, and Garland’s fully restored birthplace is open to the public.

But the must-see area is the Forest History Center, a state historic site and a living history museum that recreates life in a turn of the century logging camp. Costumed interpreters guide visitors through a recreated 1890s logging camp to tell the history of the industry and its relevance to today’s economy.

Northern Minnesota was the right place, at the right time, for a logging boom. Accessible timber was very valuable after the Civil War. The treeless prairies were being settled by farmers and they weren’t happy with sod buildings for long. They wanted boards for building houses, barns, fences, chicken coops and other farm buildings, and nearby Minnesota was full of trees.

According to frontier logic, the forests were inexhaustible. So, from about 1870 well into the 1930s, the great timber rush lasted. It marked one of the bigger land grabs -and wastes – in American history.

The exhibits and history fascinated me, but I wanted to learn about the timber era from somebody who’d been there.

“I’d love to talk to a real lumberjack who’d worked in the woods before World War II,” I remarked to the person at the information desk. “Too bad the old timers are gone. “

The Grand Rapids Logging Museum has a recreated turn of the century logging camp. (Grand Rapids Logging Museum photo)

“Most of them are,” she replied. “But we have a list of those who are still alive. Some are in retirement centers, and some of them aren’t as sharp mentally as they used to be.”

I quickly got the list, and started making some phone calls. The first two calls were blanks – one man was clearly too senile, and the other didn’t want to talk to me.

“Try Bill Byers,” the interpreter suggested. “He’s sharp as a tack, and helped us set up some of the displays. We call him whenever we have questions about the logging camps.”

Byers, at the time 84, of Grand Rapids, spent 66 years in the timber business, and is a living encyclopedia of logging lore. He was, the interpreter said, usually happy to talk to anyone with an interest in the timber business. A quick phone call got an invitation to visit, so I headed for his home.

Once most of Minnesota was covered with forests, but extensive timbering cleared the land and the farmers soon followed. As Minnesota grew up after the Civil War, adventurers, speculators, drifters and entrepreneurs of all sorts converged on the state to take part in a giant land grab.

Many immigrants, mainly Scandinavian, were lured to the area by the attraction of free homestead land. Others came for the timber. All a fellow had to do was cut the trees off his land, float the logs down the river to the sawmill, and he had an instant profit. Some people paid for their land with that first timber harvest.

Byers lived alone in a faded yellow house with his 12-year-old sheepdog. The interior of his house has the particular slovenly appearance commonly associated with long-time bachelors. He lives mostly in one room during the winter to conserve heating costs.

I liked Bill immediately. He had a hearty handshake, a ruddy complexion and strong hands and shoulders from a lifetime of hard work in the woods. His attitude about housework, like mine, has to do with priorities.

“I chose to spend my time at other activities,” he gestured at the mess. “I played my first game of pool at age 72 at the Senior Citizens’ Center. I spend most of my time with the elderly.”

Byers was supposed to be placed in a nursing home in Grand Rapids in 1976, but he refused to be slowed down. The most important aspect of his life was to record an oral history of logging in northern Minnesota. He bought an expensive tape recorder, and was attempting to save what he could.

“I’m amazed at the amount of misinformation there is about that early time period in the timber industry,” Byers said. “History is supposed to be fact.”

Byers himself is quite a story. In 1914, his family moved from Missouri to Minnesota in a covered wagon pulled by horses. He grew up in the 1930s, and times were hard, and the only work available was in the logging camps. Byers signed on as a cook’s helper or “cookee” with the Minnesota Cedar Log Company.

“I was just a kid,” he recalls. “My duties included waiting tables in the cook shack, washing dishes, turning flapjacks and bus boy type activities.”

The lumber camps back then were small villages, complete with cookshack, bunk house, privy, barns, blacksmith shop, company store, and saw sharpening shed. The Minnesota Cedar Log Company camp was two days by train from the nearest town. There was no doctor in that town so the cookee – or whoever felt up to the task – was also the doctor and dentist.

By the time he was 17, Byers had set broken arms, tended various cuts, scrapes and bruises, and even tried to pull teeth.

“All I had to work with was a pair of pliers,” he said. “It is virtually impossible to pull a tooth with pliers, but some of the jacks got into such pain they asked me to try.”

The logging season usually started after the first snow fall. The buildings were built during the summer and the camp was located in the middle of a huge tract of timber.

During the season, the usual schedule was to work 26 13-hour days each month. For that, the lumberjack was paid about $15 a month, plus room and board.

“During the Depression, loggers, would work for whatever they could get hired on for, and be glad to get it,” Byers said. “It cost them about two months’ wages to buy the woolen clothes they needed to keep warm in the woods.”

Still, men applied for work every day. Some were so desperate they’d work for nothing. Some immigrants would work for room and board because they didn’t speak English, he added, couldn’t get another job and wanted to stay in this country.

“I’ll have to say, though, that most timber companies were honest and fair with their employees,” Byers said.

Most of the loggers were Scandinavian, Byers said, usually Finns, Swedes and Norwegians. The log drivers, a group of men who “herded” logs down the rivers, tended to be French, he added, because they were smaller and fast on their feet.

In the logging camp pecking order, the cook ranked high. A camp with a poor cook would have a hard time attracting and keeping good employees. At his first job, Byers and his co-workers fed 200 men five meals a day, seven days a week.

“Standard fare was some sort of meat, potatoes, coffee, beans and usually prunes,” Byers said. “All the fruit was dried and prunes were considered a necessity for loggers. A 30-gallon coffee pot was kept simmering all the time. ”

After three years in the kitchen, Byers changed jobs and started handling horses. The logs were skidded out of the timber on big sleds, and one important job was to ice the roads.

Byers drove the tank wagon. It had a sprinkler system heated by a wood stove. Every morning, he filled the tanks and iced the road surface. The sprinkler was followed by the timber haulers, who took the logs to the banks of a nearby river.

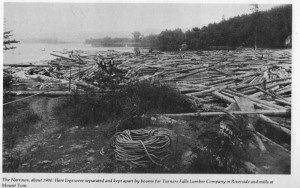

When the ice melted in the spring, the logs were floated downstream to the nearest sawmill. The log drives themselves were a kind of wooden cattle drive. Loggers with spiked shoes jumped from log to log in an effort to keep them all pointed downstream.

Occasionally logs would jam somewhere along the line and stop the whole drive. Sometimes dynamite had to be used to break up the jam and get the logs headed downstream again.

Byers rode the wanagan, a floating cook shack, clerk’s office and storage area on a wooden raft.

“The work wasn’t considered extremely dangerous, even though the best drivers couldn’t stay out of the water all the time,” Byers said. “The Mississippi was a good river for a log drive because it was wide, deep and had few rapids.”

Byers rode on the wanagan, a floating office/headquarters, during log drives. (Minnesota Historical Society photo)

The end of the log drives usually marked the end of the winter logging season. Most of the loggers would go back to their farms or whatever they did during the off-season. The loggers would get paid off at the end of the drive, and for many, that was the signal to go a spree at the nearest tavern.

Though many people think lumberjacks were rowdy, hard-drinking brawlers, Byers insists that stereotype is incorrect.

“The jacks were grossly misrepresented,” he claims. “There were always a few loners who couldn’t get along with anyone, but for the most part, there was hardly any trouble in the camps.”

Byers said he witnessed “maybe two or three fights” in the logging camps during his years in the industry. Most jacks, he claimed, were farmers who worked in the woods during the winter to support their families, or immigrants who were saving up to buy a farm or business.

“I’d guess less than two percent fit the ruffian stereotype, but they all seemed to enjoy the reputation!” Byers said. “The truth is, life in the woods tended to be rather dull during the winter months.”

Still, for many loggers, spring and getting paid meant it was time to get rowdy.

“I was too young to drink when I started logging, but I could go into the taverns and watch,” Byers said. “I’ve seen men, after a few drinks, attack others from behind, and I’ve seen brawls where men were kicked in the face after they were down. After seeing some of those fights, I knew there were many lost, lonely souls.”

After a hitch in the Army in World War II, Byers ran his own camps for several years, then operated a sawmill until he was 72. Until he was 83, Byers cut his own firewood every year.

Then he got too busy to take time out from his schedule. Byers has been busy putting his own recollections on tape, so someday someone can use them for reference.

He has appeared on several radio shows with his stories of the lumberjack days, and is frequently contacted by the logging museum to identify equipment and materials and give talks.

He has also contacted as many of the oldtimers as he can find, and has attempted to record their stories.

“Many times the interviews are not worth recording on tape,” he admits. “Many of the people are senile and can’t remember much. Others think you want to hear a good story and they’ll give you one, but there is not a great deal of fact involved.”

Most authorities agree that the golden age of Minnesota logging was over by the time chainsaws came into widespread use in the 1940s. There are few genuine lumberjacks left, which lends particular urgency to Byers’ oral history efforts.

“I just hope somebody records us old timers before we’re all gone,” he said. “Otherwise, part of our history dies right along with us old men.”

To read the rest of Downriver, click here.

Leave a Reply