Us equipment users find good gear and use the hell out of it. That’s what happened to the Buck folder I bought 40 years ago this month.

by Leon Pantenburg

In the summer of 1976, I was a new Iowa State University graduate, completely broke and unemployed with no real prospects of landing a high-paying job. But I had world traveler plans and was wild to experience the wilderness and mountains of the western United States.

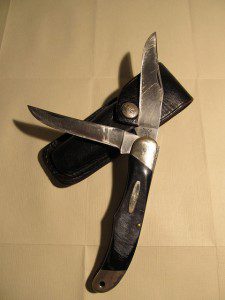

I bought my Buck folder in 1976. (thefloridasteampunker.blogspot.com photo)

That summer, I backpacked several hundred miles in Wyoming and several parts of the Sierras in California. Hiking the complete length of the John Muir Trail fanned my backpacking interest and curiosity into a complete and uncontrollable addiction. (Read my trail journal.)

I had to invest in gear. Balancing needs with my budget meant some serious comparison shopping had to happen. (FYI: Minimum wage in Iowa at the time was $1.60 an hour.)

I spent $105 on a Kelty Tioga backpack and $85 for a hollowfill sleeping bag. My boots cost $25 (as best I recall) and came from the War Surplus Store in Powell, Wyoming.

There was a lot of shopping around before I bought a new Buck 317 folder for $25 on August 31, 1976, at the Ace Hardware Store in Lovell, Wyoming. That knife was carried and used extensively until I opted for a rigid blade and bought a Cold Steel SRK in 1991.

I wore out the boots and the sleeping bag. But a good knife, properly cared for, is virtually impossible to wear out or screw up. Before it was honorably retired in 1991, that Buck was my indispensable tool.

That folder went on backpacking trips in Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains, the Pryor and Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming, the Thorofare Creek Trail loop in Yellowstone, numerous hikes in California, which included Death Valley, and on countless canoe trips, including one through the Okeefenokee Swamp in Georgia.

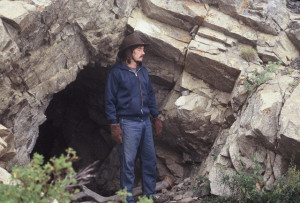

A much younger Leon at a silver mine in the Beartooth Mountains in Montana.

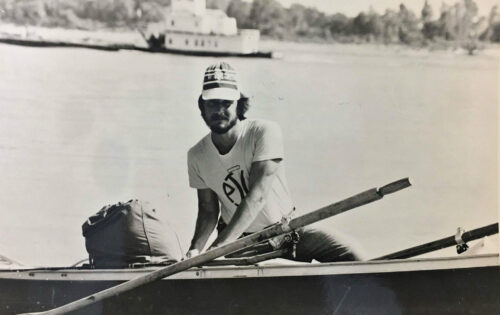

That Buck was my everyday carry knife on my 1980 six-month, end-to-end Mississippi River canoe voyage. (Check out the river story.) The blades stayed sharp, despite being used for virtually everything a canoe knife can be used for.

The knife rode in a leather sheath on my hip, and I put it on with my pants in the morning, and removed it when I crawled into my sleeping bag at night. Along the Mississippi, a knife sheath on a belt didn’t get a second glance.

The next year, the Buck became my hunting knife when I became addicted to whitetail hunting in Mississippi. It was used on many deer, and was frequently loaned out at deer camp because I kept it razor sharp.

Then the Buck accompanied me on backpacking and bicycling trips and deer hunts in Virginia and upstate New York. Though the knife was used constantly and never let me down, it was replaced with a Cold Steel SRK when I took up backcountry big game hunting in Idaho in 199o.

This Cold Steel SRK served me well for more than 20 years.

Here’s the specs of the Buck:

Steel: Buck’s standard blade material, according to the Buck Company, is 420HC because it combines “excellent wear resistance of high carbon alloys with the corrosion resistance of chromium stainless steels.” An exclusive heat-treat process for superior corrosion resistance, the company claims, creates “excellent tensile strength, hardness and wear resistance.”

Handle: The injection molded black valox handle fit my hand well. Even though it frequently got bloody and slimy, the handle didn’t get slippery and unsafe to use.

Blade points: The clip and drop point on the blades proved to be excellent choices. The clip was used most often, with the most common task being slicing apples and spreading peanut butter on crackers. The drop blade was kept razor sharp and was used mostly for cleaning fish. Over the years, that blade got thinned down a lot from constant sharpening.

No lock blade: In the early 70s, the Buck 110, with a lock blade, was really popular. Deer hunting buddies of mine still use theirs. It’s an excellent knife, though a little heavy for my tastes. I understand that a lockblade MIGHT be safer, but otherwise, I didn’t really see the need.

I don’t trust the safety on a firearm or the lock on a folder’s blade. Use any lockblade like it doesn’t have a lock.

Size: The Buck was too big and thick to carry comfortably in a pocket, but I didn’t care. I always carry my pocketknife in a belt sheath if at all possible. My Swiss Army Knife Tinker rides on my belt every day, and it’s not a big knife.

Blade length: Both blades were about 3-1/2-inches long, which is about the ideal size for a do-it-all knife. I’d prefer a shorter blade for small game processing and whittling, and a longer blade for butchering. The best blade length depends on what you’ll be using the knife for.

While the Buck worked very well in the southeast, I had some reservations about it continuing as my western hunting knife. Here’s why I went to a rigid blade hunting knife.

Backpack hunting in the Idaho backcountry requires pack weight be kept to an absolute minimum. Kill a deer or elk several miles back in the mountains and you’ll have a real job getting the meat out before it spoils.

You need a lightweight, but sturdy knife, with the most efficient design possible. Any butchering gear must also double, if necessary, as survival tools.

Folders are more fragile than rigid blade knives. If a folder is going to break, it will do so at the hinge. Murphy says that will happen at the worst possible time.

And chances are, if you’re ever going to get into a survival situation, it will be in the backcountry, and you may need that knife desperately.

So the Buck was retired with honors, and for several years, it remained in a box with several other retirees. (These included my Mississippi River fillet knife, a Shrade lockblade folder and several others.)

And then it disappeared, somehow. I don’t have a clue where it went, unless the Buck got lost during a move.

I’d give a lot to find that grungy, well-used pocket knife. You don’t want to give up on stuff that works.

Please click here to check out and subscribe to the SurvivalCommonSense.com YouTube channel, and here to subscribe to our weekly email update – thanks!

Leave a Reply