My dad’s shotgun was a handmade drilling he brought home from World War II in Germany.

It’s my personal connection with the last days of WWII.

by Leon Pantenburg

My shotgun generally gets a few looks. The gun was originally my dad’s, and it is a pre-World War II 16-gauge side-by-side drilling, with an 8×57 rifle barrel underneath. It is ornately engraved with hunting scenes, and signed by gunmaker Franz Kettner. (Here is more information about Franz Kettner.) The stock is Circassian walnut burl (I think). The gun shows some honest use and wear.

This pre-World War II drilling was my Iowa pheasant gun.

When I was a kid, the drilling was nothing special. It was my upland gun, and I shot the hell out of it. Iowa farmers, like my dad, use tools, and most considered a gun to be a tool. They were used for putting down injured farm animals, eliminating gophers in the garden, crows that were harassing chickens or the occasional varmint that needed eliminating. Every farmer had a shotgun, and a .22 rifle.

But Iowans are also avid hunters, and shotguns are used for hunting everything from quail to deer. When Dad quit hunting, I used the 16 for hunting pheasants in standing corn. It has tight chokes, and patterns Number 6 shot really well.

Dad never talked about his service, except a story about a Louisiana chicken dinner. But even as a kid, I knew the veterans’ stories were important, and I gathered bits and pieces as I could. Later, as a trained journalist (Iowa State University, class of 1976) and a newspaper editor in Washington D.C., I discovered the national archives, and researched individual unit records.

I also got the letters Dad sent to his sister, Edna. Dad’s letters were, of necessity, devoid of any military specifics. I read them all, and they were mostly about life at Camp Shelby. Once he got to Europe, there weren’t many letters.

He did wryly comment in one letter, that “I captured eight Germans all by myself.” During the last days of the war, many German soldiers, desperate to escape being captured by the Russians, surrendered to the first Americans they came across. But other than that, most letters were folksy tales of training and questions about how folks were doing back home

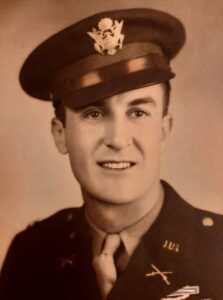

Dad, at home on leave,before shipping overseas in 1944.

Tracking dad’s service was challenging. He enlisted in the Army in 1941, and trained troops at Camp Shelby, MS. He was sent to Europe shortly after D Day as a Military Policeman. He was in Patton’s Third Army that went to the relief of the besieged city Bastogne, Belguim.

Then he got transferred to a motor transportation group, where he escorted supply convoys, and was finally promoted to Captain and company commander of a front line infantry unit. Casualties had been extreme – an estimated 300,00 Americans were killed in the European theater in about a year. To add to the tracking confusion, different American units might swap shoulder patches to confuse German efforts to track troop movements.

Anyway, here is the story of my Dad’s shotgun, as accurately as I can re-create it.

Germany, 1945

The Battle of the Bulge had been over for several months, and Patton was driving toward Berlin. Spring was coming and parts of Germany were a lot like Iowa – it had the same rolling hills, black soil and similar farm implements. The people looked the same too – Story County, Iowa had been settled by Germans and Scandinavians, and the German people even looked like the folks back home.

But the fighting wasn’t over.

In the autumn of 1944, according to War History Online, the Nazis instigated a plan to establish active forces behind enemy lines as the Allies pushed through Germany. It was called Operation Werewolf (Werwolf in German) and accomplished very little apart from its propaganda effect.

The Werewolf troops reputation spread around the Allied forces and was the reason used by the Allies to detain thousands of Germans after the war. They did so to prevent an uprising, although the likelihood was minimal. Rumors or not, Dad’s outfit was ordered to “confiscate and destroy all weapons” when they came to small villages and towns.

Dad was wearing this uniform the night he met my mom at a church dance.

“There would be a pile of all sorts of rifles and shotguns as high as your waist, a block long,” Dad told me. “We destroyed beautiful rifles and shotguns worth thousands of dollars.”

The standard procedure, he said, was to grab the (unloaded) gun by the barrel and smash the stock against the ground until it broke. Then, the barrel was stuck in the towing hook of a half-track and bent into a U.

Anyway, the soldiers were working their way down a stack of firearms when Dad came to the drilling. For some reason, this one stuck out. Maybe it was because of the stock fit. He threw it to his shoulder, and it felt right.

“I don’t know why I picked that particular shotgun out. It just fit me,” he said. “I figured I could do some shooting with it.”

Dad was a superb marksman with a pistol, rifle or shotgun. He had learned to make every shot count as a kid growing up during the Depression. He had a single shot .22, and hunted every night after school. A box of 50 .22 shorts was expected to bring in the equivalent number of rabbits and squirrels. Often times, Dad’s hunting success was directly related to what the family had for dinner that night.

Dad improvised this scrap aluminum trigger guard before a deer hunt.

Because of his shooting skills, Dad was kept at Camp Shelby to teach rifle and pistol marksmanship. He did that for about a year, and he and the other instructors had unlimited ammunition and target practiced every day.

Dad passed up dozens of shotguns during the last months of the war. Looting was strictly forbidden, and could bring a court martial. But the powers-that-be sometimes looked the other way. And Dad really liked that drilling.

So, Dad reasoned, the idea was to take firearms away from potential Werewolves. And the best way to put that drilling out of commission, was to send it to Ames, Iowa, where it would be securely locked up in a gun safe.

The forearm got cracked while riding under a Jeep seat.

Dad disassembled the shotgun into three pieces. The stock and receiver were stored in his pack. The forearm was stowed under a jeep seat, where it got cracked somehow. The barrel was wrapped in canvas, and kept in a Half Track. The shotgun rode in those three places until the end of the war.

Along the way the barrels got a few scratches, but other than that, the gun arrived safely in Iowa. Dad mailed it home in separate pieces, and my grandpa put it together.

Dad hunted hard with the drilling. In 1952, he killed a doe with it in one of Iowa’s first deer hunts since the Depression. (His hunting blade was a Hitler Youth knife.) The trigger guard got broken somewhere during transit, so Dad made a makeshift scrap aluminum guard. He always intended to make a better one, but never did. After some 80 years, there is no point in worrying about it now.

Top: His kids bought Dad a commemorative brick at the U.S. Army Museum in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Left: My left foot is adjacent to Dad’s brick. The museum is in the background. Center: The World War II memorial in Washington D.C. Right: Alvin York’s helmet he wore on the day he earned the Meadl of Honor.

Today, the old drilling resides in my gun safe. It has not been retired. Its stock fits me like a glove, and I enjoy the conversations it starts.

I killed several Oregon chukars and pheasants with it, a few years back, and as always, I will hunt with it this fall. The old gun will be taken out, shot and then thoroughly cleaned, like I do every year.

There are still a couple boxes of fives and sixes Dad bought in the 1960s at Montgomery Ward’s, and they still fire like they were new.

And I figure I can do some shooting with it.

Please click here to check out and subscribe to the SurvivalCommonSense.com YouTube channel – thanks!

Leave a Reply